for Harryette Mullens

I just can't seem to make my leg straight. I should try harder to tighten my standing leg, to make it a strong foundation. I ought to be more flexible. He wishes I wasn't so needy. He never comes over to adjust me. He always talks about his sister during class. Sometimes he annoys the hell out of me. Once in a while what he says is an epiphany. However it is obvious that he is trying to distract us. His overall tendency has been to tell us not to drink water. The consequences of which have been me leaving to room to cry by the water cooler. He doesn't appear to understand that if we don't hydrate we will pass out. If only he would make an effort to remember what it was like at the beginning. But we know how difficult it is for him to connect with strangers. Many of us remain unaware of our potential. Some who should know better simply refuse to touch the floor with their palms. Of course, their perspective has been limited by their pain. On the other hand, they obviously feel entitled to be here. We know that this has had an enormous impact on our stress levels. Nevertheless their behavior strikes me as self-involved. Our interactions unfortunately have been drenched in sweat.

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Thursday, December 15, 2011

Brooklyn Rail Publication

So "Abstract Painting" ended up getting published in The Brooklyn Rail. Perty sweet.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Friday, November 25, 2011

As If Nothing Had Happened

My mother’s father, who we called Gigi, was blind for the last five years of his life. He lost eyesight in his first eye when he was playing tennis with my aunt and got hit in the face with the tennis ball. There was something about a detached retina, a product of the blow from the ball whose speed was a product of my aunt’s sporty, competitive nature. For a few years after this my mom told me that he acted as if the whole thing hadn’t happened, continuing to drive his car, but with his head cocked to the side to give his one eye the full view of the landscape.

A few years later, when his other eye went dark, he became frail and thin. I learned the phrase “skin and bones,” which I liked to repeat whenever Gigi was mentioned in front of someone who didn’t know him. “He’s all skin and bones,” I’d say. To me it sounded like a disease, but I failed to realize how it reflected his stubbornness. His wife had been dead a long time. His one daughter lived close by, my mom and our family lived two hours away. But he would get along on his own, as if the whole thing hadn’t happened.

I remember the weekends we’d visit—usually just mom, Thomas, and me. There was the Rice Krispie Cereal I’d eat his kitchen counter, which had a funny taste that I came to realize later was because I had been eating out of the same box for five consecutive years.

There was the warm bowl of water and my grandfather’s fingers and mom with an emory board, giving him a manicure.

There was the vintage slot machine that continued to accept dimes and to let you win back your earnings 90% of the time.

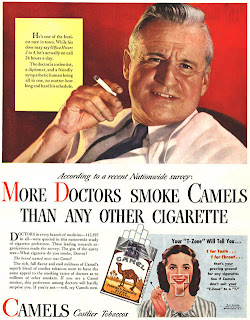

There were the lighters, placed strategically around the house so that wherever Gigi was he could still be smoking a cigarette. He had burn holes in his clothes, in his chair, his couch, his green robe, even a big black char on the bathroom floor from what I imagine must have been a small fire.

The way my brother and I used to fight about who got to light his next cigarette. And the way Gigi would hold it, poised on the edge of his lips. And how I’d gingerly strike the dial and produce the flame. The time I gave him his cigarette backwards and lit the filter. The way my mom refused to believe in second hand smoke, saying like she later would about Global Warming, that people were paranoid and such a thing didn’t exist. How we’d come home from the weekend, unpack our suitcases, and find our clothes caked in the smell.

The way, late at night when Thomas and I had been tucked into the twin beds in the guest room, I’d creep out of bed to see Mom sitting on the back porch, looking at the lights of the San Bernardino Valley, drinking a glass of wine and smoking a cigarette with her father.

A few years later, when his other eye went dark, he became frail and thin. I learned the phrase “skin and bones,” which I liked to repeat whenever Gigi was mentioned in front of someone who didn’t know him. “He’s all skin and bones,” I’d say. To me it sounded like a disease, but I failed to realize how it reflected his stubbornness. His wife had been dead a long time. His one daughter lived close by, my mom and our family lived two hours away. But he would get along on his own, as if the whole thing hadn’t happened.

I remember the weekends we’d visit—usually just mom, Thomas, and me. There was the Rice Krispie Cereal I’d eat his kitchen counter, which had a funny taste that I came to realize later was because I had been eating out of the same box for five consecutive years.

There was the warm bowl of water and my grandfather’s fingers and mom with an emory board, giving him a manicure.

There was the vintage slot machine that continued to accept dimes and to let you win back your earnings 90% of the time.

There were the lighters, placed strategically around the house so that wherever Gigi was he could still be smoking a cigarette. He had burn holes in his clothes, in his chair, his couch, his green robe, even a big black char on the bathroom floor from what I imagine must have been a small fire.

The way my brother and I used to fight about who got to light his next cigarette. And the way Gigi would hold it, poised on the edge of his lips. And how I’d gingerly strike the dial and produce the flame. The time I gave him his cigarette backwards and lit the filter. The way my mom refused to believe in second hand smoke, saying like she later would about Global Warming, that people were paranoid and such a thing didn’t exist. How we’d come home from the weekend, unpack our suitcases, and find our clothes caked in the smell.

The way, late at night when Thomas and I had been tucked into the twin beds in the guest room, I’d creep out of bed to see Mom sitting on the back porch, looking at the lights of the San Bernardino Valley, drinking a glass of wine and smoking a cigarette with her father.

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

Fatalism: Good or Bad or Inevitable

I really didn’t know what to think of Lyn Hejinian's The Fatalist for the first twenty-five pages until I read an essay explaining how the language in the book was literally taken from a year’s worth of Hejinian’s correspondences (emails included). The idea of someone looking at a year of their life and watching the stream--how things came to be--which events lead to other events, is really intriguing. Every once in a while, I look through a decade-worth of Facebook pictures. Don't we all?

The definition of fatalism is “the belief that all events are predetermined and therefore inevitable.” According to the dictionary, the end result of a belief in fatalism is “a submissive attitude to events.” This attitude could be interpreted as either positive or negative (or I suppose both). A negative reaction would say there is nothing you can do to change the trajectory of your life, which is kind of scary. For someone who’s dealt with hip pain and surgery and all that comes with that for the past two years, the idea that none of it will make a difference, the idea that “I was always meant to have hip problems,” is terrifying. But a more positive view reminds me of a line in Kathleen Graber’s book of poems The Eternal City, which says, “Tell yourself it's simple: this is where it's been heading all along. Tell yourself something you have no faith in has already begun to occur." Like, I have faith that my hips are getting better. All the pain and worry and anxiety has been leading to this moment of faith, where I finally believe that “I was always meant to be healed.”

I don’t understand the outcome of studying Lyn Hejinian’s year of correspondence. It’s hard for me to place myself into someone else’s head, especially when words and phrases have been deleted. Who was she talking to, for example, when she wrote, “The children now admit they are violent” (Hejinian, 29). But the language is striking and beautiful-- “prose is not necessarily not poetry” ("Barbarism," Hejinian, 323).

But the experience of reading this book has caused me to reflect on my own experience. And without having known Hejinian’s premise--the year’s email correspondence--I could not have come away with the same sense of meaningfulness. To relay what I mean, I offer an example. At one point in the year, Hejinian happened to write a line about destiny. Not just a “this is where we ended up” kind of destiny, but a reflective thought about journey and the unknown. And then later, for at least one of her readers (me!), that line would become the crux of the book the writer didn’t know she was writing:

“Perhaps the trip

will be purposeless. Destiny is simply a good excuse for experience.”

How does one not come away with a sense of Oh.

(Image taken from heavy-videos.blogspot.com)

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Moved

On 10th and Broadway

you recited the Nicene Creed

and said you believed in God

and the Spirit.

I thought you might even take communion.

We joke about the unleavened bread.

How good it tastes when

you haven't eaten for hours.

But it was too soon for that.

We bowed our heads.

From the corner

your lips moving

I did notice that.

you recited the Nicene Creed

and said you believed in God

and the Spirit.

I thought you might even take communion.

We joke about the unleavened bread.

How good it tastes when

you haven't eaten for hours.

But it was too soon for that.

We bowed our heads.

From the corner

your lips moving

I did notice that.

Friday, September 30, 2011

My Shelf, My Shelf

John Donne:

My God, my God, Thou art a direct God, may I not say---a literall God, a God that wouldest bee understood literally, and according to the plaine sense of all that thou saiest? But thou art also (Lord I intend it to thy glory, and let no phrophane misinterpreter abuse it to thy diminution) thou are a figurative, a metaphoricall God too: A God in whose words there is such a height of figures, such voyages, such peregrinations to fetch remote and precious metaphors, such extensions, such spreadings, such Curtaines of Allegories, such third Heavens of Hyperboles, so harmonious eloquutions, so retired and so reserved expressions, so commanding perswasions, so perswading commandments, such sinewes even in thy milke, and such things in thy words, as all prophane Authors, seeme of the seed of the Serpent, that creepes, thou art the Dove that flies.

Me:

My shelf, my shelf, you are a book shelf, dare I say it--a handmade shelf, a shelf that would be overlooked easily, and mistaken for a normal place for all of the books. But you are also (shelf I want you just to listen, and let no idiot outsider change our topic of conversation) you are an art-piece, an underrated Ikea block: a shelf in whose stacks there is such an amount of stories, such writings, such authors whose words bring images and profound meaning, such colors, such spines, such inspiration of genius, such first editions of classics, so demanding recognition, so humble and so assumedly normal, so sideways slanting, so slanting sideways, so leaning over towards the desk, and yet tall in your stance, as all wayward writers, seem to be bent towards the ground, like willows, you are the shelf of life.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Deep Peace

It was the week before my surgery. I had been home from New York for three days when my mom and I decided to go to the beach. We packed up the Volvo with towels, water bottles, and sandwiches, and drove up the 101 freeway to Ventura.

We spread out our blankets on the empty beach, next to the rock pile so Mom could rest her back against the heated boulders. I got up and walked towards the water. Mom shivered as I rose. “Brrr, won’t it be cold?”

I shrugged. I was going to swim. I was going to use my body before God knew what was about to happen to it.

The water rushed at my ankles, and a wave rolled in against my thighs, and I stepped forward until the cold was swirling around my stomach. And then I plunged under, kicking my legs, I took a breath of warm air and then pumped my arms against the coming waves until I got past the break. When the water calmed, I turned over onto my back and floated, rocking with the surf, the sun beating on my belly and chest.

As I made my way back to shore, I scanned the beach for my mom. I wasn't wearing my glasses, and it was hard to see her, but then I spotted a form of person by the rocks right in front of me. Standing up in the foamy water, I laughed and did an overly dramatic mime of me looking for someone, and then pointed my finger right her and laughed out loud again. Like, hey, I didn’t see you, but you’re right there!

I walked out of the water and towards the sand, and realized I was pointing at a stranger.

* * *

We arose early, before the sun. My parents were sitting in the front seats of the car, and I was in the back, twisting my hair with my fingers, taking deep, long breaths.

“Are you okay?” my dad asked.

I nodded.

The nurse called my name, and I gave my parents a quick glance before following her from the waiting room and into the back. The surgeon emerged wearing scrubs. He was holding a black sharpie in his hand. “I need to mark you up, okay?”

I unbuttoned my pants and pulled one side down my thigh. He wrote something on my skin with the pen.

“How are you feeling?” he asked.

He was bright eyed, his hair still wet from the shower; I was his first operation of the day. I imagined he had gone for a run that morning. I wondered if he knew what it was like to never be able to run again.

“Ready,” I said.

The nurse lead me to the bathroom where I was to change into a robe, place my clothes into a plastic bag, and pee into a cup. “We have to make sure you’re not pregnant,” she explained, smiling.

Once I was changed they led me into another room. The anesthesiologist was there, along with two other assistant surgeons. They were also wearing scrubs and hats like shower caps. They asked me if I’d eaten anything that day, Are you quite sure? Nothing? They asked me if I'd had anesthesia before, Yes, tooth surgery. While they were asking me, there was a woman lying on a bed nearby sobbing, Oh my god, oh my god, I can’t take it. Please, I can’t stand it. My heart rate, which was being read by a monitor to my left, sped up. That won’t be you, the surgeons said.

They asked me to sign the dotted line, the one saying I would authorize an amputation if the need arose, and they walked me into the operation room where they told me to lie back on the table, Wow, you’re tall, where they pricked me with needles until they found a good vein, where I could hear my heartbeat suddenly fill the room, quick and sharp, You must be cold, they said. My legs were shaking. They put something over my face. And the room went black.

There is a Celtic prayer —

Deep peace of the running waves to you.

Deep peace of the flowing air to you.

Deep peace of the quiet earth to you.

Deep peace.

(Image from http://higginsbecas.livejournal.com/)

We spread out our blankets on the empty beach, next to the rock pile so Mom could rest her back against the heated boulders. I got up and walked towards the water. Mom shivered as I rose. “Brrr, won’t it be cold?”

I shrugged. I was going to swim. I was going to use my body before God knew what was about to happen to it.

The water rushed at my ankles, and a wave rolled in against my thighs, and I stepped forward until the cold was swirling around my stomach. And then I plunged under, kicking my legs, I took a breath of warm air and then pumped my arms against the coming waves until I got past the break. When the water calmed, I turned over onto my back and floated, rocking with the surf, the sun beating on my belly and chest.

As I made my way back to shore, I scanned the beach for my mom. I wasn't wearing my glasses, and it was hard to see her, but then I spotted a form of person by the rocks right in front of me. Standing up in the foamy water, I laughed and did an overly dramatic mime of me looking for someone, and then pointed my finger right her and laughed out loud again. Like, hey, I didn’t see you, but you’re right there!

I walked out of the water and towards the sand, and realized I was pointing at a stranger.

* * *

We arose early, before the sun. My parents were sitting in the front seats of the car, and I was in the back, twisting my hair with my fingers, taking deep, long breaths.

“Are you okay?” my dad asked.

I nodded.

The nurse called my name, and I gave my parents a quick glance before following her from the waiting room and into the back. The surgeon emerged wearing scrubs. He was holding a black sharpie in his hand. “I need to mark you up, okay?”

I unbuttoned my pants and pulled one side down my thigh. He wrote something on my skin with the pen.

“How are you feeling?” he asked.

He was bright eyed, his hair still wet from the shower; I was his first operation of the day. I imagined he had gone for a run that morning. I wondered if he knew what it was like to never be able to run again.

“Ready,” I said.

The nurse lead me to the bathroom where I was to change into a robe, place my clothes into a plastic bag, and pee into a cup. “We have to make sure you’re not pregnant,” she explained, smiling.

Once I was changed they led me into another room. The anesthesiologist was there, along with two other assistant surgeons. They were also wearing scrubs and hats like shower caps. They asked me if I’d eaten anything that day, Are you quite sure? Nothing? They asked me if I'd had anesthesia before, Yes, tooth surgery. While they were asking me, there was a woman lying on a bed nearby sobbing, Oh my god, oh my god, I can’t take it. Please, I can’t stand it. My heart rate, which was being read by a monitor to my left, sped up. That won’t be you, the surgeons said.

They asked me to sign the dotted line, the one saying I would authorize an amputation if the need arose, and they walked me into the operation room where they told me to lie back on the table, Wow, you’re tall, where they pricked me with needles until they found a good vein, where I could hear my heartbeat suddenly fill the room, quick and sharp, You must be cold, they said. My legs were shaking. They put something over my face. And the room went black.

There is a Celtic prayer —

Deep peace of the running waves to you.

Deep peace of the flowing air to you.

Deep peace of the quiet earth to you.

Deep peace.

(Image from http://higginsbecas.livejournal.com/)

Thursday, August 4, 2011

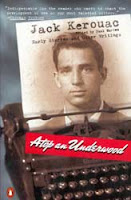

What Are You Reading, Rachel Hurn?

As many of you know, and most of you don't, I have been something of an invalid this summer. Therefore, my commitment has been to read a book a week. Below are the titles I've read, and also a few that are stacked on my nightstand, being fondled with almost as we speak. I highly recommend each, for very different, and also not very different reasons.

Saturday, July 30, 2011

I Like This Woman: Also, Antics of My Mother

My mom was on the way to her book club, when she noticed that instead of reading “In the Garden of Beasts,” which is a story about a family in pre-war Berlin, she actually read “Beast in the Garden,” which is a true story about a pack of cougars that invade a small town in Colorado.

When playing “Guesstures” last night, instead of guessing “kneel” my mom guessed “genuflect.” When it’s her turn, one should keep in mind that she uses the same motion for “embrace,” “cold,” “warm,” and “zombie,” which is to hug her arms around her body.

When playing “Guesstures” last night, instead of guessing “kneel” my mom guessed “genuflect.” When it’s her turn, one should keep in mind that she uses the same motion for “embrace,” “cold,” “warm,” and “zombie,” which is to hug her arms around her body.

Sunday, July 17, 2011

White Bread

Mom remembers the day Thomas was asked to draw her portrait. He was in the first grade at Emmanuel Presbyterian, and the teacher told the children to sketch a picture of their mother for Mother’s Day.

“I looked mulatto in that picture,” Mom says.

We’re eating dinner at the dining room table. Mom has made rice, collard greens, and lemon chicken. The collard greens have too much bacon in them, and every time someone asks what we were having for dinner she yells, “CALL-ard greens!” with a southern accent.

“All the other pictures of all the other moms were just white bread, white bread, white bread,” Mom says, pointing at invisible women with her spatula, “but I was brown.” She laughs. “I thought it was great.”

Thomas is poking at the parmesean rice on his plate. Dad is at the head of the table, “What kind of rice is this?” he asks.

“It has cheese in it,” I say.

“Well I don’t like it.”

Thomas swallows. “I just remember thinking that nobody’s white. Like nobody’s totally white like paper. That’s all.”

“Well I thought it was so great,” Mom says, still laughing. “I looked different.”

“What kind of cheese did you say?” Thomas asks.

“Parmesean,” I respond.

“I don’t like it,” he says. “Sorry, Mom. I just don’t.”

“It’s okay, Thomas. Neither do I,” Dad says. “I don’t like the rice either.”

Mom shrugs.

She goes on to tell us about the day Thomas came home with the drawing. How he was sitting in the back seat of the car when she drove up to Nellie’s house, and Nellie’s daughter Robin, who was then in her twenties, came running out to say hello. “Show Robin the picture,” Mom had said. “Thomas drew a picture of me in school,” Mom explained out the window.

Thomas stuck the paper through to Robin, and she looked at it and tried to stifle a laugh.

"You’re black, Sigrid! Did you know? You’re black in this picture!”

Dad stops putting food in his mouth and looks up. “What, you thought Nellie was your mom or something?”

Thomas rolls his eyes.

“Well that’s what Robin said,” Mom interjects. “She was laughing because it looked like me, but also like Nellie.” She pauses. “I wish I still had that picture.”

Thomas puts his fork down and shakes his head. “I know, I know, I feel bad about that every time I think about it.”

“Feel bad about what?” Dad asks.

“I tore up that picture, and I feel horrible about it.”

“Oh you were little, Thomas,” Mom says. “It’s okay. You didn’t know.”

“No, I was a bad person.” Thomas is still shaking his head.

“You tore up the picture?” Dad asks. His fork is poised in the air, inches in front of his face. “You really tore it up? Why would you do something like that?”

“Because he was little and mad and didn’t know,” I say. “Stop asking stupid questions.”

(Painting "White Bread" by Wayne Thiebaud.)

Friday, July 1, 2011

Birdwatching

We are through working for the day when I go to the backyard to watch my mom finish her drink. Before I sit down I take the cigarette from her hand and take a long drag, then place it back between her fingers. In front of her is a tall glass of ice and limes and the remains of a Vodka tonic. I sit down on the seat next to her and lean against the back cushion, my face bent dramatically towards the sky.

"Oh, I can't go on," I say. "It's too much."

"I know what you mean," Mom says, taking a drag of her cigarette. She looks down at the stub between her fingers. "I've gone out," she laughs, reaching forward to take the pack of matches from the table. "I guess I smoke too slow."

Mom lights the end, sucks in, and holds out the cigarette for me. I take it again, surprised that I'm not enjoying the taste as much as I used to.

"You know I came out here with the binoculars to look for that bird nest," she says.

I don't know what she's talking about. I give her a look.

"There are a family of birds," she explains, "at least I think. We can hear them chirping pleasently right by our window every morning." She smiles to herself, staring off into the distance, most likely listening to the sound of birds.

"I think I found the nest actually, over by the neighbor's house. It looks like a swallow nest or something."

"What does a swallow nest look like?"

"Oh, you know, kind of like made out of mud or something. Instead of sticks. It's really quite impressive. Do you want to see?"

She stubs out her cigarette, and I follow her over to the side of the house. She's taking slow steps along the rocks, the binoculars held up to her face, staring up at the neighbors' house. "There," she says, "I think it's right there. Here," she hands me the binoculars, which are large and heavy and used to belong to her father. "You take a look."

I peer through the lens, adjust the focus, and slowly inspect the eves of the house. "You know it would look really weird if they came home and saw us doing this."

Mom laughs. "Do you see it?"

"I don't know. I see something. But it doesn't really look like a nest."

"Right, it looks like it's made out of clay or something," she says excitedly.

"Mom, there's nothing up there but a pipe from the bathroom."

"A pipe?" Mom takes the binoculars from my hand. "Let me see that." She stares up at the house again, her neck craned.

"Ha!" she laughs and looks at me. "So it is a pipe. And I thought they were just clever little birds who make nests out of clay."

Saturday, April 30, 2011

Long-Distance Runner

The fact is, I don’t want to have this surgery. And I certainly don’t want to imagine what it will be like if it goes wrong. I don’t want to be the unfortunate disable people barely remember. I bitterly wish I could be back to the way I was before the accident, and not really so athletically different, necessarily. I was trim and fit and strong, not any good at team sports but mostly unhindered when it came to running. That was one way I took after my college roommates, the track stars. I was never talented like them, but I was very eager, very dedicated. Even now, if I could trust my body a little more, I know there’s a lot I could do.

I don’t have to fault myself for feeling this way. The Lord wept in the Garden on the night He was betrayed, as pastors have said to me many times. “Who will free me from the body of this death?” Well, I know the answer to that one. “We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye.” I imagine of kind of ecstatic pirouette, a little bit like going for a long run on the beach when you’re so new and fit that your body almost doesn’t know about effort. The apostle Paul couldn’t have meant something entirely different from that. So there’s that to look forward to.

I say this because I really feel as though I’m failing, and not primarily in the medical sense. It’s more about the weeping emotion, the worry. And I feel as if I am being left out, as though I’m some straggler and people won’t remember to stay back for me. I often think about what I can’t do, comparing myself to them. I’ll be on my bicycle, happily riding around the inner loop in Prospect Park, and the sun will be shining, and my legs will be pumping, but all the while I am staring at the runners. I had a dream like that the other night. In the dream, my legs wouldn’t move.

Saturday, April 23, 2011

Blank

I remember that old Baptist church that my parents took us to, the hard wooden pews, the large cross bathed in light behind the pulpit, looking ten times as remarkable as it would have if a light had not been shining on it. That was always a major part of my idea of a church, the cross. When I was a child I stared up at it until I got tears in my eyes. I had watched the older women do this, stare into the light, shake their heads down, stoke their arms. It seemed the highest compliment one could give to God—deep distress over his mangled son.

Because we were Baptist the cross was blank to signify the resurrection. I had to imagine Christ hanging there, a crown of thorns wound round his head, his chest heaving.

Pastor Hasper stood before us, a lanky six foot four. I thought it fitting his name rhymed. That indeed he had been called to the ministry, the same way some friends of our, the Doctors, were called to the medical field, each child growing up to become Dr. Doctor. My name didn’t rhyme with anything.

Monday, April 11, 2011

Electric Ice

What a day, you said.

We were in Coney Island. It was my first time.

It was also seventy degrees for the first time since I’d been in California.

Who knew winter would last this long?

I guess it’s easier when things are new.

We walked along the boardwalk—the rides were closed.

Based on the signs we were six days too early.

Shopkeepers stood on metal ladders with paintbrushes in their hands, preparing for the harvest.

You stood next to me at the walrus exhibit, preparing for the launch—a moment when the bulbous creature would brush his whiskers against the glass by your face, push off with his fins, and fly backwards, upside-down, like a fat, white torpedo.

The blue rectangle of water before us—the creepy shine of the light against your profile—made you look like an ipod advertisement.

I snapped a picture, which you later threatened to delete.

You thought you’d get sick from the clams. It was lent—I had given up meat, you had given up bread—Nathan’s hot dogs “Since 1912” were out of the question.

We’re not even riding a roller coaster, I assured you.

Instead we walked backwards.

Pushed off the wall of piss by the bathroom sinks,

And floated to the man with the stained cover-alls.

I have 3.98, you said. It’s all you, baby.

The soft serve was called “electric ice.”

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

The Church on Munjoy Hill

For Randy Henry, who died on March 20, 2011

One evening in early fall while I headed towards town, I stopped to look inside the old stone building near the lighthouse on Munjoy Hill. A few men were standing at the door, and one of them was dragging out a sign that read, “Evening Episcopal Service, Six o’clock, All Welcome.” I looked down at my watch. It was 5:55. “Hello there,” the tallest man with white hair said. I would come to know him as Pastor Jim, an Episcopalian minister who traveled from a town twenty miles outside of Portland to lead the candlelit, Sunday evening service. I didn’t come up with an excuse or stop to think about my other plans. I simply slipped inside.

The church had been converted into a theatre company, so the stage where Jim stood to preach rotated with props for whatever show was being performed. At that time of year it was “On Golden Pond,” and while Jim spoke the liturgy and told us of our location on the church calendar, fishing rods and galoshes stood behind him in the shadows.

Every Sunday night I would walk to that church and join the other twelve members in the arena seating. We sang from Episcopalian hymnals, while Tom, a shy man with uneasy musical talents, led on the piano. I met Portlanders, people who I would run into regularly while living in Maine. There was an empty-nested couple who were rooming their daughter’s friend for free while she went to nursing school; a young mother who brought her baby every week, cradling him in her arms; a soft-spoken girl named Sarah who I would regularly see walking by the water in the mornings. For communion, we would arise and join Jim on the stage. Standing in a circle, he would come to us one by one, placing the bread on our tongues, holding the cup of wine to our lips. “Do this in remembrance of me.” Sometimes a woman preached but mostly it was Jim who wove deep, stirring narratives about the world we inhabited, and the people we were supposed to become. When I asked him where he got his stories, he responded simply that he too was a writer.

Later, I attended Jim’s book club and walked in the room to find big bottles of wine set out on folding tables. Along with crumb cake and sugar cookies, they were part of the refreshments, and women with fat fingers stuck corkscrews into their tops and pulled them out with a loud pop. I sat next to two ninety-year-old sisters—who would later become subjects of my first published article—and they informed me that Jim had graduated from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. A few months later, I would attend this same club, this time in Jim’s living room, where he would give us a screening of the movie “Lars and the Real Girl,” about a man who falls in love with a blow-up doll. The same old woman would lean in close to me, holding my arm, “I always like what Jim has to say, but I’m not sure about this one.”

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

One Nice Thing

I drove to D.C. for the weekend with Jonathan, and before I left my mother told me to be sure to check for a box that was scheduled to arrive. “It’s your Valentine,” she said, “and it’s kind of a big box.” I immediately assumed she meant she was sending a painting—a watercolor of three girls playing in the surf—that my grandmother painted before I was born. I thought about sending the painting to myself the last time I was home, but it was too expensive to ship.

My mother isn’t a very good gift giver. For Christmas, my family pulled names and decided to get their person one nice thing, no more than forty dollars. Instead of buying me a nice leather address book or a sweater or something, my mom went to Staples and bought a bunch of little journals and notebooks, a pedometer that didn’t work, a pair of sparkly dress socks. At first I just opened them and thanked her, but then a few days later I realized that there was no reason why I couldn’t return those things, so I did. Mom didn’t seem too hurt. “I’d rather have one nice thing,” I explained. She nodded her head.

When I got back from D.C., my roommate was sitting on the couch reading, and she gave me a hurt expression. “Your box came,” she said, looking at the floor. I looked down to see a big, square cardboard box whose top had been smashed. “I’m a little worried,” my roommate said, “because the box says fragile.” Trying to ignore my slight feeling of disappointment--inside this square could not possibly be a painting--I cut open the flaps, moved the tissue paper aside, and lifted out a long cylinder. Pieces of glass fell from the paper and onto the floor. “Oh no,” I moaned, “it’s broken.” My mom had attached a note inside. “These candlesticks are from Egypt,” she said, “and they’re glass (I had to ask the clerk) so be careful.”

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

Ad Reinhardt, "Abstract Painting"

Right now, in the MOMA, there is a painting by Ad Reinhardt from 1963 called “Abstract Painting.” To the people shuffling through the rooms on a January Sunday, it is a black square. They turn their heads to glance at it briefly as they walk by, probably thinking of the red and black Pollack in the next room, or thinking nothing.

They have to look closer. They have to stop shuffling. They have to stop talking.

They have to stare.

They have to take off their glasses, even. They have to stop thinking about their stomachs and the restaurants serving discounted buffalo wings in Times Square. They have to be quiet.

Be quiet. Be quiet. Be quiet. Be QUIET!

This painting is not so hard to get, really. I point it out to a heavy-set woman in red glasses and a blue striped shirt. She’s Midwestern. She’s here for the day. She’s here to see Pollack.

“Do you see it?” I ask.

She waits. “Oh, yes.”

“Yes, you see,” I point with my finger. She follows my finger with her eyes. “There, and there,” I say, shifting my weight, changing my gaze from one corner of the painting to another. “This one is especially purple.”

“Thank you,” she says.

I smile. She walks away.

I sit down on the black, rectangular bench, and then he comes and sits down next to me. Silently, he studies my face. I wonder, can he see them? Can he see the purple squares?

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Two Blogs Coalesce

Photography by Karen Parker

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2011/01/the-run-on-stony-stratford.html

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

Saturday, January 1, 2011

Freedom

I biked across my parent’s town today.

In five miles I passed two lemon groves and

five churches. Instead of broken bottles on the pavement,

or pieces of furniture set out on stoops,

there are avocados, whole ones, fallen off the trees

and rolled into the street.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)