My mother’s father, who we called Gigi, was blind for the last five years of his life. He lost eyesight in his first eye when he was playing tennis with my aunt and got hit in the face with the tennis ball. There was something about a detached retina, a product of the blow from the ball whose speed was a product of my aunt’s sporty, competitive nature. For a few years after this my mom told me that he acted as if the whole thing hadn’t happened, continuing to drive his car, but with his head cocked to the side to give his one eye the full view of the landscape.

A few years later, when his other eye went dark, he became frail and thin. I learned the phrase “skin and bones,” which I liked to repeat whenever Gigi was mentioned in front of someone who didn’t know him. “He’s all skin and bones,” I’d say. To me it sounded like a disease, but I failed to realize how it reflected his stubbornness. His wife had been dead a long time. His one daughter lived close by, my mom and our family lived two hours away. But he would get along on his own, as if the whole thing hadn’t happened.

I remember the weekends we’d visit—usually just mom, Thomas, and me. There was the Rice Krispie Cereal I’d eat his kitchen counter, which had a funny taste that I came to realize later was because I had been eating out of the same box for five consecutive years.

There was the warm bowl of water and my grandfather’s fingers and mom with an emory board, giving him a manicure.

There was the vintage slot machine that continued to accept dimes and to let you win back your earnings 90% of the time.

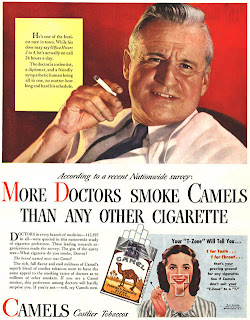

There were the lighters, placed strategically around the house so that wherever Gigi was he could still be smoking a cigarette. He had burn holes in his clothes, in his chair, his couch, his green robe, even a big black char on the bathroom floor from what I imagine must have been a small fire.

The way my brother and I used to fight about who got to light his next cigarette. And the way Gigi would hold it, poised on the edge of his lips. And how I’d gingerly strike the dial and produce the flame. The time I gave him his cigarette backwards and lit the filter. The way my mom refused to believe in second hand smoke, saying like she later would about Global Warming, that people were paranoid and such a thing didn’t exist. How we’d come home from the weekend, unpack our suitcases, and find our clothes caked in the smell.

The way, late at night when Thomas and I had been tucked into the twin beds in the guest room, I’d creep out of bed to see Mom sitting on the back porch, looking at the lights of the San Bernardino Valley, drinking a glass of wine and smoking a cigarette with her father.

Friday, November 25, 2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

I remember those days. I still feel that way about second hand smoke and global warming. lol

ReplyDelete